Existential and philosophical effects and consequences

To my knowledge, this is the first philosophical system with the characteristics of a theorem that uses, as basic axioms, some corollaries of the “axiomatic model/theorem of the infinite Universe“.

The conclusions it reaches are not of the type: “I think that …”, “I believe that …”.

These have nothing subjective and reach conclusions that leave you breathless, but that are incontestable because the entire system presents itself in the form of a theorem that has the status of demonstration.

Corollary

A corollary is nothing other than a proposition that follows directly and logically from a theorem or hypothesis.

If the theorem has the status of a proof or the hypothesis is indisputable, then the corollary that follows from it is nothing more than an obvious and immediate consequence of a statement that has already been proved and becomes, in turn, indisputable.

Generally, corollaries provide further information or details about the main theorem and help to better understand its implications and consequences.

They are often used to extend and/or apply the main theorem to specific cases or to prove secondary but important results within the specific theory or context that is to be explored.

The conclusions of the ‘axiomatic model/theorem of the infinite universe’, with the status of a demonstration, which are used in this paper, are essentially:

I. There is a Universe infinite in time, infinite in the amount of mass/energy and therefore infinite in space;

II. This infinite Universe contains, necessarily, an unlimited number of cosmos; an unlimited number in what we consider to be our past, in what we consider to be our present[1] and in what we consider to be our future;

III. the “cause-and-effect principle” cannot be disputed;

IV. Because of the ‘cause-and-effect principle’ mentioned in III., the existence of ‘free will’ is denied. [Free will’ cannot exist].

To these four corollaries, a fifth argument must be added, which has to do with an actual theorem. This is the ‘tireless monkey theorem’, inspired by the second lemma of the Borel-Cantelli theorem.

—- * —-

[1] Two events can only be considered simultaneous, according to the theory of special relativity, if they are at the same point in space and at the same instant in time in a given inertial reference system. Systems that are simultaneous in one reference system may not be simultaneous in a different reference system. Events that appear to occur simultaneously from one point of view, may be considered to be non-simultaneous from another point of view moving relative to it.

1

There is a Universe that is infinite in time, infinite in the amount of mass/energy and therefore infinite in space.

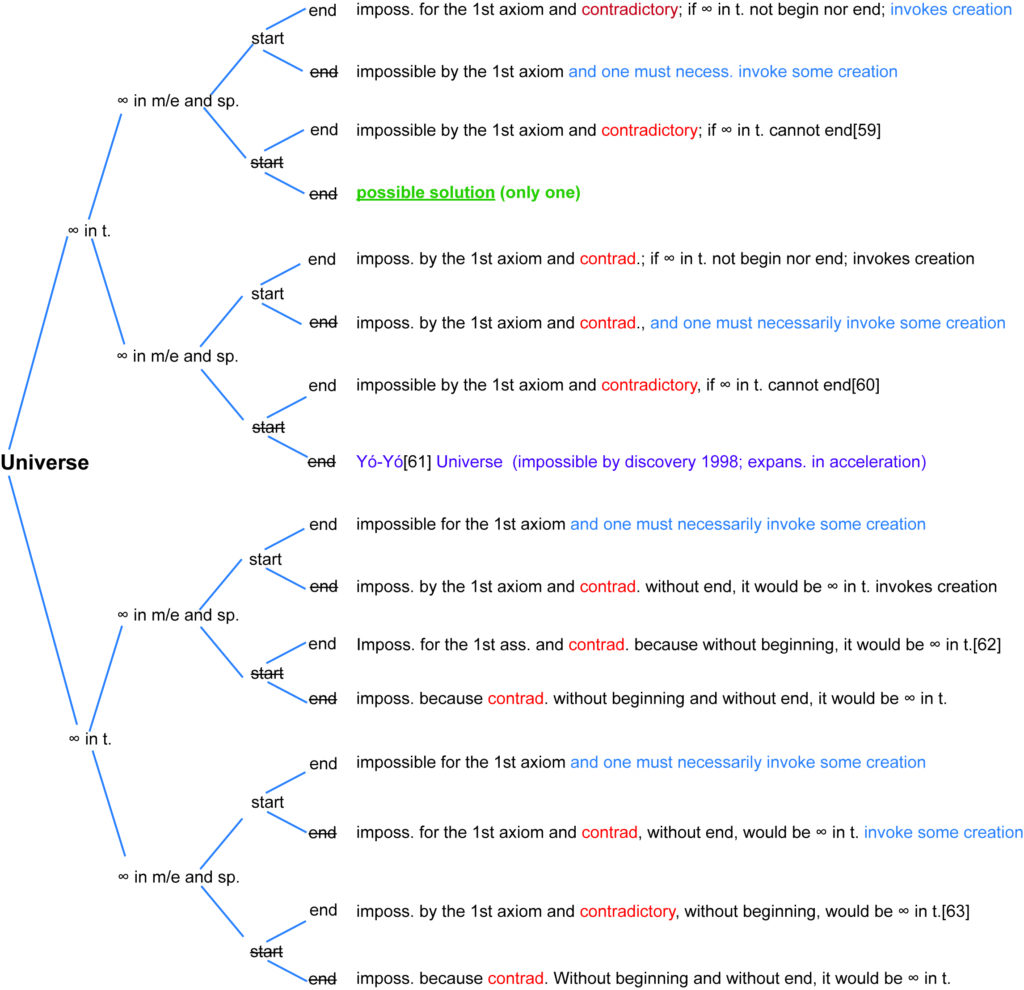

On page 25 of the ‘axiomatic model’, I have depicted a dichotomous tree diagram[1] that allows us to visualize, in a relatively simple way, what the possible types of ‘Universe’ are.

It must be said that the type of universe in which we live has a substantial impact both on our laws of physics and on a philosophy that flows from this cosmological structure.

The structure and characteristics of our Universe determine the conditions under which life can exist and how it can evolve, and they also influence how we interpret and understand the reality around us.

Furthermore, our understanding of our Universe and our place within it is closely linked to the physical laws that govern it.

Physics provides us with an important and indispensable framework for understanding the natural phenomena we observe, and the scientific theories we develop are fundamental to our knowledge of the world.

Philosophy, on the other hand, attempts to explore deeper questions about the nature of reality and our place in it. Cosmology provides interesting insights into fundamental philosophical questions, such as the origin of our Universe, its purpose and our place within it.

Ultimately, the typology of our Universe is of fundamental importance to our understanding of the world and to the development of our philosophy and vision of this world. Ongoing scientific and philosophical research allows us to explore this Universe of ours in depth and enables us to discover new perspectives on the reality around us.

In the dichotomous chart below, I have considered four characteristics, four peculiarities, that allow us to identify the possible solution(s) of our Universe.

These four characteristics and their respective negations are:

I. “infinite universe in time” and its negation: “finite universe in time“;

II. “universe infinite in the quantity of mass/energy” and its negation: “universe finite in the quantity of mass/energy“;

III. “universe that has a beginning” and its negation: “universe that has no beginning“;

IV. “universe that has an end” and its negation: “universe that has no end“.

The dichotomous tree that emerges thus contains 4 x 4 solutions, i.e. 16 solutions.

[1] A dichotomous tree graph is a graphical representation of a set of data or relationships branching dichotomously, i.e. divided into two parts. Each node of the tree is divided into two branches representing the two possible directions or choices to be taken. This type of graph is often used to visualize even complex decision-making processes in a simple way.

2

In the dichotomous tree, which follows, the 16 different solutions were examined, considering that we are dealing with:

- Universe infinite in time (∞ in t., without limits) or with its complement a Universe finite in time (

∞in t.); - Universe with an infinite amount of mass/energy and space (∞ in m./e. and in sp.) or with its complement (

∞in m./e. and in sp.); - Universe with a beginning or its complementary, the one without a beginning;

- Universe with an end or its complement, the one without an end.

[3] A Universe that has no beginning, cannot have an end. Let us imagine that we are dealing with the set of natural numbers (0, 1, 2, 3, … ∞). Now imagine that we start not with ∞ (which is not a number; which is not a number. For more details, see ∞ in limits), but with any large number. We subtract 1 and then subtract, again and again, a unit from the number obtained and so on, without end. At this point, we could make use of an algorithm, the following: once we have reached (with this procedure) a certain number, of our choice and between ∞ and ω (omega, an arbitrary value chosen at will), a unit is added to that ‘any large‘ number and we repeat, all over again, the procedure, with this new beginning (this procedure has no term and is always permissible because we are dealing with infinity). This algorithm will ensure that ω will never be reached. The same applies to the reverse process i.e. ω +1+1+1+… you will never reach ∞ (which is not a number).

The procedure (-1, -1, …) is therefore infinite because, since it is possible to make the starting number larger and larger, ω will never be reached. Not only will ω never be reached, but neither will any natural number, even a large one chosen at will. To conclude, a Universe without a beginning cannot have an end. Let us imagine replacing natural numbers with seconds (e.g. 1= one second, 2= two seconds, … ); the time elapsed between a number of seconds tending to ∞ and any number ω of seconds, chosen at will, will necessarily tend to infinity and therefore this ω will never be reached. This argument highlights a contradiction in the sequence considered (beginning – end) and invalidates it. Our Universe, therefore, cannot be associated with the idea of semi-route (∞… end of semi-route). Someone, following in the footsteps of the great mathematician Georg Cantor (*1845 †1918), might say: ‘I see it but I can hardly believe it’.

[4] See footnote 60.

3

The graph on the previous page shows that, of the sixteen hypotheses formulated regarding the type of Universe, one and only one is possible, and therefore all the others are excluded.

– Ten of these hypotheses (Hypotheses 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, and 16) are to be excluded, since they contain a sequence of conditions that includes some contradiction within it, and this makes the hypothesis unacceptable. Hypotheses 1, 5, 10, and 14 also make use of an unacceptable concept of creation;

– Four of these hypotheses (2, 6, 9, and 13) invoke the unacceptable concept of creation, which makes them unacceptable;

– One of these hypotheses (Hypothesis 8) proposes a Yo-Yo cosmological model, i.e. a finite amount of mass/energy alternating Big Bangs, followed by Big Crunches, in a continuous and endless manner.

The latter solution is not acceptable, since a finite amount of mass/energy would be completely depleted, following continuous and perpetual emanation (since the Universe is necessarily infinite in time) emanation of photons of light, x-rays, gamma rays, radio waves, Hawking radiation, magnetic fields, Higgs fields, …

It is not sensible to imagine that the energy given off, during the expansion period, after the Big Bang, could return to its complete totality at the moment of the ‘big crunch’.

[Any ‘big crunch’ would, of necessity, have to wait for the last and farthest of the emitted photons (or some other sub-atomic particle) before implementing the next ‘Big-Bang’.][7].

This last consideration can only invalidate the hypothesis of a possible ‘Yo-Yo Universe’.

Incidentally, the Yo-Yo cosmological model would in no way justify the two recent discoveries:

– the 1998 one concerning the escape acceleration of the galaxies in our Cosmos, which suggested the idea of a negative pressure from within our Cosmos being responsible for this acceleration. This idea has taken the name ‘Cosmological Constant/Dark Energy’. The term ‘dark energy’ was coined in 1998, by US astrophysicist Michael Turner, at a scientific conference;

– the most recent one, from 2020, which refers to the fact that not all galaxies have the same acceleration towards the outside of our Cosmos. This discovery made US astrophysicist Gerrit Shellenberger, who was in charge of announcing this discovery, say and write: “Based on our observations of clusters we may have found differences in the speed at which the Universe is expanding, and this finding would go against one of the most basic assumptions we use in cosmology today (Lambda CDM model) .”

the Universe, therefore, can only be endowed with an infinite amount of mass/energy.

This circumstance makes it possible, among other things, to explain two recent discoveries, namely that of 1998 (escape acceleration of the galaxies in our Cosmos) and that of 2020 (not all galaxies have the same acceleration outwards from our Cosmos). The ‘axiomatic model’, in fact, justifies these accelerations (including the differentiated ones) by replacing the hypothetical push from within our Cosmos, the so-called ‘cosmological constant’ (already invoked, improperly, by Einstein) with differentiated forces of attraction, which come from outer space with respect to this Cosmos of ours.

[7] If this were not the case, then each Big-Bang would be different and inferior to the previous one in terms of the amount of mass/energy. That is, there would be a continuous loss of the quantity of mass/energy that, in an infinite time, would cause the total exhaustion of a hypothetical and absurd ‘Yo-Yo Universe’.

4

The solution proposed in point 4. of the dichotomous tree graph on the previous page thus results:

The only possible solution is that of a Universe (endowed with an infinite amount of mass/energy)[8] without beginning and without end, an ‘infinite system in time and space that, although not closed, possesses the characteristics of a perfectly isolated system’, in which and only in its totality does the law of conservation of mass/energy apply, without exception.

The term ‘Yo-Yo Universe’ was coined by the pupils of a fifth grade class at the Verrès high school, where I often gave lessons, starting in 1990. These monothematic lessons essentially concerned mathematical topics and dealt with concepts that were not easy for the pupils to digest, such as the ‘concept of limit’, which even recent graduates in mathematics find difficult to understand in its deepest sense.

I make this (solidly documented) assertion without wishing to offend anyone.

The fact is that there is something peculiar, of course there is, in this concept of the limit, because it was not understood during antiquity (including ancient Greece). It was not understood by the good mathematicians of India, nor, during the period from the 8th to the 14th century, by the Arabs. It was not understood by our great mathematicians of the seventeenth century, nor by those of the eighteenth century. We have to wait until the first half of the 19th century, to finally have, by Cauchy (*1789 †1857) and with some additional clarification by Weierstrass (*1815 †1897), the definitions of limit that we use today[9].

Going back to the high school class that enunciated the term/concept ‘Yo-Yo Universe’, I do not remember exactly which school year it was. All I know is that it was still a few years away in 1998, the year in which, following the observation of some ‘Type Ia’ [10] Supernovae in distant galaxies, some American astronomers made a sensational and surprising revelation: “The expansion of our Cosmos did not correspond to what the cosmological models of the time assumed, because it was accelerating“[11] . It is useful to point out that this discovery, the result of careful observational activity, is in agreement with what the ‘axiomatic model’ announced, namely that after a prolonged phase of deceleration, following the initial Big Bang, the galaxies in our Cosmos could only begin to feel the effect of the gravitational fields of masses present outside our Cosmos, and therefore a phase of acceleration, towards these gravitational centers, has begun.

[8] the Universe can only be endowed with infinite mass/energy. If it were not so, then its (finite) mass/energy would end up being completely exhausted, following the perpetual emanation (since the Universe is infinite, in time) of: light photons, x-rays, gamma rays, radio waves, Hawking radiation, …

[9] Cauchy and Weierstrass played a crucial role in formalizing the concept of limit, making it rigorous and understandable, which paved the way for a number of subsequent developments in analysis.

[10] Type Ia’ supernovae (first a / one a) originate from the explosion of a white dwarf, which is what remains of a small to medium mass star that has completed its life cycle and within which nuclear fusion has ceased. The luminosity generated by its explosion is such that it exceeds, for us distant observers, that of the entire galaxy to which it belongs.

[11] This announcement earned the authors of this discovery the Nobel Prize.

5

During my talk/lesson we consider each of the two hypotheses that were in vogue at the time, namely:

I. If the amount of mass/energy of our Cosmos was less than a value which, for the sake of convenience, we call ‘k’, then our Cosmos should not have ceased its expansion and would have undergone a gradual cooling and the death of all its life forms.

II. if, on the other hand, the amount of mass/energy of our Cosmos was not less than that value, then our Cosmos should have undergone a gravitational collapse and would have ended up recomposing on itself and therefore a return to the situation that generated our Big-Bang should have occurred, and this repetition of the phases of expansion (following each Big-Bang) and its subsequent collapse should have (for both Poincaré’s recurrence[12] theorem and the second lemma of the Borel-Cantelli theorem) repeated itself infinitely and without interruption.

Once the illustration of the second hypothesis was finished, a loud, heartrending cry was heard in the classroom.

Screaming, shouting and expressing her infinite despair was a pupil in that class who had evidently seen, in that second hypothesis, a repetition and an infinite number of times of her certainly not happy life experience.

The pupil was immediately surrounded by her classmates and teachers who tried, in ways they already knew, to calm her down and bring her back to a minimum of tranquility and serenity.

This concerted action, of those who lovingly surrounded her, paid off and after a certain amount of time, which to me seemed a very long time, the pupil began to breathe again with less breathlessness and with the eyes of someone who had suffered a tremendous and horrible beating, she laid her head in her arms, on her desk.

I felt guilty about that very sad event, which I had not foreseen at all.

I have not forgotten and I think I will never forget what happened that day in Verrès. I still remember it today as if it had happened yesterday.

On 4 February 1998, news emerged that American physicists Saul Perlmutter and Adam Riess and Australian physicist Brian Schmidt had ascertained that our galaxies are undergoing accelerated expansion and have been so for more than four billion years.

At the time, I had not yet come to the conclusions of the recent ‘axiomatic model’ and it seemed to me that this announcement might rule out the hypothesis of a ‘Yo-Yo Universe’.

[12] Poincaré’s recurrence theorem or fundamental theorem of statistical mechanics, holds that in a closed mechanical system, all particles will sooner or later return to occupy exactly the same position and move in exactly the same way as before. This theorem was proved by Henri Poincaré (*1854 †1912) in 1890.

6

I would have liked to communicate this to that pupil at the Verrès high school, but I could not remember her name and above all I did not know her real life situation at the time. That is why I did not seek any contact with that pupil.

Today, with hindsight, I am of the opinion that I would not have known how to do anything other than give a fleeting illusion that would soon vanish and be a further disappointment to her.

In fact, this illusion has since been belied by the recent ‘axiomatic model’ which, although structured very differently from the ‘Yo-Yo’ model, shares with it certain conclusions due, essentially, to the ‘second lemma of the Borel-Cantelli theorem’ and Poincaré’s ‘recurrence theorem’.

I admit that, like that pupil at the Verrès secondary school, I did not like some of the conclusions reached by the ‘model’ either and that is why I sought ways to refute its content.

I did not know how to contest its logical-mathematical structure, composed of deductions, inferences, logical implications, demonstrations, … (Even my high-level mathematical friends couldn’t do it after reading it.). So I tried to demolish at least one of the two axioms I had identified as starting points for what was in effect a theorem. The result was a total failure, as I came up with two ‘demonstrations’, one for each axiom, which confirmed, without a shadow of a doubt and unequivocally, their validity (see ‘axiomatic model’).

An infinite number of cosmos

The limitless dimensions of our infinite Universe lead us to consider an intriguing and at the same time attractive concept: ‘the existence of an unlimited number of cosmos: unlimited in the past, unlimited in the present and unlimited in the future’. Each of these cosmos can only be an entity in its own right, with its own physical laws, constellations and life forms.

This image of the Universe, conceived as a container for an infinite number of different realities, invites us to reflect on how small this ‘observable universe’[13] of ours is (a sphere whose radius measures approximately 46 billion light years and constitutes only a small part of our entire Cosmos).

Beyond this ‘observable universe’, a proper and finite subset of our Cosmos, our capacity for investigation and inspection is finite. We must therefore resign ourselves to the fact that we are but a tiny, tiny part of a Cosmos that is, in turn, nothing more than an infinitesimal of our infinite Universe.

In conclusion, reflecting on the infinite Universe and unlimited cosmos helps us understand how extraordinary the reality in which we live is and pushes us to explore new horizons of thought and knowledge.

—- * —-

[13] The observable universe is the portion of the universe that is visible to observers on Earth. It is all that we can see or detect through observational instruments such as telescopes or satellites. Because light has a certain speed and the universe expands over time, there are parts of the universe that are so far away from us that the light emitted by them has not yet reached us, making them invisible to us at the moment.

7

The tireless monkey theorem

For point I. (There is a Universe infinite in time, infinite in the amount of mass/energy and therefore infinite in space), by Poincaré’s ‘recurrence theorem’[14] and by the second lemma of the Borel-Cantelli theorem (tireless monkey theorem), the repetition of our life cycle, exactly as we have experienced it and as we are experiencing it takes shape and becomes a certainty.

This repetition depends on the fact that what we have lived and are living represents a real and possible solution, in this infinite Universe of ours, and therefore can only be repeated and without end.

More generally, all non-impossible solutions can only have and have taken place, forever and ever!

With regard to the generalization of this concept and especially with regard to the assertion that all infinite solutions are possible, this is not self-evident, let alone self-evident, since every solution is possible and repeatable if and only if there are no objective impediments to its realization, to its materialization.

The question is whether there can really be such impediments, given that there is nothing to prevent us from thinking that this Universe, of which we are a subset in our own right, could be not only infinite in the direction of the large, ever larger, but also in that of the small, ever smaller, i.e. without any end, even in this direction.

The ‘tireless monkey theorem’ has its roots in the second lemma of the Borel-Cantelli theorem. This formulation of the problem was given by Félix-Édouard-Justin-Émile Borel (*1871 †1956) himself.

This theorem finds application in a wide variety of fields: in physics and engineering, in marketing and advertising, in economics and finance, in computer theory, …

The question concerning the ‘tireless monkey’ is actually a ‘thought experiment’ that imagines a monkey and his typewriter.

This indefatigable monkey types, at random and without pause, the keys of his keyboard and thus the letters of the alphabet (including punctuation) for an ‘infinite’ amount of time.

According to the theorem in question, if the monkey continues to type the characters on its keyboard ad infinitum, it can only produce every possible combination of letters and thus texts, including the Divine Comedy, The Betrothed, One Hundred Thousand Little Jars of Ice, the Coûtumier of the Aosta Valley (1588), … and each of these infinite times!

This theorem illustrates the concept of infinite probability, i.e. that if you have a sufficiently large number of random attempts, you will eventually get even the most curious and surprising event. This concept has to do with the nature of randomness.

Let us try to simplify, as much as possible, the problem to be solved.

[14] See footnote 12 of this paper.

8

Given a keyboard of “t” keys (this “t” represents the number of keys) and a written text, to be played, of “b” keystrokes, the probability of not getting it in “n” (independent) attempts is:

[(1–1/tb )]n and thus the limit for n → ∞ (to read: for n tending to infinity) takes the whole expression to 0 (zero).

Sometimes, in calculating probability, when the analysis of a problem situation presents some considerable difficulty, one prefers to study the behavior of its complement, if this is easier to understand and solve.

Once this value is found, its complementary to 1 is determined and this complementary represents exactly the value of the probability sought.

Since tb (in non-trivial cases[15]) has a value greater than 1, then (1/ tb) will have a value between zero and one (excluding zero and excluding one), i.e. “0,…“, with this “0,…“>0,

So (1 – 0,…) is a number less than 1 and greater than zero, i.e. “0,…“. But a number less than 1 and greater than 0 raised to a number tending to infinity, tends to zero and therefore its complement tends to 1, i.e. certainty!

The four corollaries (I. II. III. and IV.) have the value of indisputable axioms, and these axioms make it possible to draw up, by means of inferences, logical implications, reasoning, demonstrations, etc., a veritable theorem endowed with the status of a demonstration.

This theorem makes it possible to elaborate a philosophical framework that has nothing to do with subjective suppositions, such as: “I think that …“, “it seems to me that …“.

—- * —-

Time

For more details on this subject, it is useful to see or review the chapter “Time” of the “axiomatic model/theorem of the infinite Universe“.

See chapter ‘Time’ of the ‘axiomatic model/theorem of the infinite Universe’.

That of ‘time’ is not an absolute idea that applies equally to the entire ‘infinite Universe’ but (with Einsteinian relativity) takes on an alternative role, namely that of a parameter that is different, depending on the reference system chosen and that: reference systems, endowed with different gravitational potentials, have ‘times’ that flow differently[16] .

If we then also consider the implications of this concept, such as the “twin paradox” or the effects of time dilation in the proximity of massive objects, a fascinating world of philosophical discussion and reflection opens up.

[15] The expression t raised b is never greater than one when t is between 0 and 1 and b is less than or equal to zero.

[16] St Augustine (Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis): “What, then, is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I were to explain it to those who ask me, I do not know.” – (John Archibald Wheeler) “Time is the best expedient that nature has devised to keep things from happening all at once.“

9

Newton (*1643 †1727) built a veritable monument to time and space. His idea of them is of two eternal, incorruptible containers within which the events of nature unfold.

For Leibnitz (*1646 †1716), time does not exist and neither does space. They do not exist at all, nor do they exist a priori, since their existence is necessarily linked to the presence of the bodies from which the intellectual and physical elaboration of the concepts of time and space arise.

Hermann Minkowski (*1864 †1909) “… henceforth space in itself and time in itself are condemned to dissolve into nothing more than shadows, and only a kind of conjunction of the two will preserve an independent reality“. Minkowski’s ‘Minkowski spaces’ might suggest solutions regarding ‘dark energy‘ and ‘dark matter’.

For Albert Einstein, time has to do with a notion related to the concept of ‘relative’ and not ‘absolute’ as it was traditionally conceived and described. Einstein demonstrated that measures of space and time are interconnected and depend on the speed and acceleration of one object relative to another. This concept is the basis of his thinking, which revolutionized our understanding of the ‘observable universe’ and the nature of time. According to the theory of relativity, time can flow differently for observers in motion than for those at rest (special relativity), and can be influenced by gravity (general relativity). Furthermore, Einstein demonstrated that time is not a uniform and constant quantity, but can be distorted by factors such as the speed and mass of objects.

Richard Feynman, Nobel Laureate in Physics, in 1965: “Perhaps we might as well resign ourselves to the fact that time is one of the things we probably cannot define. In any case, what really matters is not how we define it, but how we measure it.“

Time can be likened to the concept of measurement: a measure we use to quantify and organise the unfolding of events in our history.

The past represents a unique experience that cannot, in any way, be changed because what has happened is now part of the past and the past cannot be altered because it has entered ‘History’ and therefore it is impossible to change or alter it. What can be done is to learn from past mistakes and try to improve future situations based on these experiences.

The present is the moment, the ‘here’ and ‘in this moment’.

It is the period of time in which we live and act, preceded by the past and followed by the future.

The present is the moment, it is the present moment, it is what we mean when we say: ‘in this moment’.

The future is a temporal dimension in which everything that has not yet happened or has yet to happen is placed.

It is a perspective of time that opens up new possibilities, new challenges and new opportunities.

The future is also the result of the choices and actions we make in the present, which influence the course of events and determine what lies ahead.

10

—- * —-

Life perception and time consciousness

Life perception and time consciousness are complex and profound topics.

Life perception refers to the awareness and understanding of one’s own existence, feelings, emotions and thoughts. This is a subjective and personal experience that varies greatly from individual to individual.

Time consciousness, on the other hand, concerns our ability to perceive and record changes in time, to be aware of the past, present and future.

Our perception of time can be influenced by various factors, such as age, experience, environment and even emotional state.

In short, life perception and time consciousness are fundamental elements of our existence and profoundly influence our perception of the world and ourselves.

They help us make sense and meaning of our reality and better understand our place in the world.

According to the ‘axiomatic model’, the perception of life and consciousness of time of each being, human or animal (for the mineral world and perhaps also for the plant world, it makes no sense to speak of perception and consciousness) ends up constituting a ‘continuum’, i.e. a seamless entity (see chapter ‘Time consciousness’).

When a tragedy occurs, i.e. when a loved one (be it a person or even an animal that one loves very much) dies, those who are fond of them feel deep grief and a sense of loss that is often difficult and sometimes very hard to overcome.

Everyone reacts as they can when faced with a sudden or even announced bereavement.

Usually, everyone tries to process and cope, in his or her own way, with what may immediately seem an irreparable and insuperable tragedy.

Time’ is a valuable ally in the process of grieving the loss of a particular loved one.

As the days, weeks and months go by, the intensity of grief usually diminishes and gives way to the memory of the good times spent with the loved one.

It is important to be able to grieve in a natural way, without forcing or denying the emotions that emerge.

With ‘time’, and only with ‘time’, one learns to live with the absence of the one who is no longer there and to find a new balance in one’s life.

It is normal that there are ups and downs during this journey, but it is important to remember that ‘time’ is an ally that allows one to heal wounds and find a new inner serenity.

11

I believe that, in this journey, it may be of some help to remember what the ‘axiomatic model’ suggests to us about ‘who is no longer there’ (see, a few lines below, the chapter ‘Who is no longer there’).

The perception of life has to do with the awareness that a conscious individual has of the world around him and, more generally, of his own existence.

This perception may vary from person to person and animal to animal, depending on factors as distinct as genetics, experience, and the environment in which one spends one’s life.

Time consciousness, on the other hand, refers to an individual’s ability to understand and measure the passage of time. This capacity is closely related to the perception of life, as the way we perceive our existence is influenced by our time consciousness.

With the ability to reflect on the past and the capacity to plan for the future, human beings have a highly developed consciousness of time.

We can remember past events, imagine future situations and perceive time in a linear way. This awareness of time allows us to make sense of our existence and make rational decisions for our future.

Animals have a different perception of time than humans. They cannot reflect on the past or plan for the future as intricately as we do. However, many animals have an amazing ability to adapt to the natural rhythms of day and night and to predict future events, such as migration or reproduction.

Ultimately, life perception and time consciousness are concepts that differ between humans and animals, but both are important for understanding our existence and our relationship with the world around us.

Who is no more

With the death of a human being or an animal, one of its cycles of life comes to an end and with it any possibility of being aware of the time that passes between the end of this cycle and the beginning of the next, however long this interval may last.

Each cycle cannot but have had an identical copy in its past and cannot but have an identical one in its future (see the second lemma of the Borel-Cantelli theorem, which gave rise to the tireless monkey theorem).

What happens (between one cycle and the next) at the molecular, atomic and especially sub-atomic level of everything that made up a human being, an animal or a plant and their environment is such that there is no possibility of remembering any details of the cycle that has just ended.

This explains why each life cycle is perceived, by those capable of perceiving it, as unique and unrepeatable. As for the ‘one who is no more’ and only for him/her, … death marks the end of his/her life cycle.

For him/her and only for him/her, this cycle will be followed, immediately and seamlessly, by the next cycle, consisting of his/her rebirth, his/her next life course and, finally, again, his/her death.

12

For this ‘he who is no more’, the time between his life cycle and the next is practically null and therefore insubstantial, because he is not perceived and therefore it is as if he did not exist.

Are we free to want what we want?

Free will concerns the ability of each person to make decisions and behave according to his or her own will and conscience, without being limited by external factors.

This way of thinking is and has long been an important topic of philosophical and theological debate.

Some currents of thought maintain that free will is a human prerogative; others claim that all, but really all, human actions are determined by environmental factors, biological factors, or even divine factors. The idea of free will undoubtedly plays an important role in understanding the notion of the responsibility of each individual and his or her ability to make a choice.

Arthur Schopenhauer (*1788 †1860) had this to say:

“We can do what we want but the limit is precisely in what we want.“

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (*1712 †1778), an 18th century Swiss philosopher, wrote in his book ‘Emile or Education’:

“We are free to do what we want, but are we free to want what we want?“

This is a pedagogical writing in which the author illustrates his philosophical and educational theories.

—- * —-

A few lusters or a hundred years

Whether a human being’s life cycle lasts a little or a hundred years only changes the number and type of experiences he or she has had, but not the quality or even the total lifespan, in infinite time, of this infinite Universe.

In fact, a few years and a hundred years are both an infinitesimal of the total passage of infinite time and therefore, both represent nothing but infinitesimals of this time. It must be remembered, however, that the sum of infinite infinitesimals (all equal to each other) ends up being an infinite time that does not depend on the duration of each infinitesimal, in fact: the sum of infinite addends, all equal to each other, can never converge and tend to any fixed and finite value, which would represent its limit.

Therefore, the sum of these infinite addends can only tend to infinity.

These considerations cannot but astonish and disconcert, since they lead to the affirmation and conclusion that each life cycle of each human being, each animal or each plant has already taken place infinite times in the past, takes place infinite times in the present, and can only take place infinite times in the future.

This view of reality makes it possible to understand the reasons why the ‘axiomatic model’ does not and cannot condemn ‘suicide’.

13

Suicide

Suicide is a delicate and very complex subject, which cannot be relegated to a purely social scourge. It certainly represents a problem, a big problem!

Its exponential growth is worrying and cannot but prompt careful and serious reflection, on the part of everyone, on the part of our entire society.

There are many and certainly many reasons that may contribute to this exponential growth.

The following list does not claim to be exhaustive:

- mental health problems, financial problems, work problems, relationship problems, …

- problems of depression, anxiety, various disorders, …

- lack of adequate support, social isolation, …

- easy access to means for suicide, such as various bridges, firearms, drugs, …

- current or past trauma, abuse, bullying, …

- …

It is certainly important to address these issues and in a serious manner.

There are many authoritative articles on this subject. There are also numerous books worth reading; see, by way of example:

“Suicide“, a book written by Émile Durkheim, one of the fathers of sociology.

Durkheim analyses the phenomenon of suicide from a sociological point of view, distinguishing between four types of suicide: selfish, altruistic, anomic and fatalistic. Durkheim explores the social causes of suicide and argues that it can be influenced by factors such as the level of social integration, solidarity and social regulation. The book provides an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon of suicide and its connection to society.

—- * —-

How do different religions view ‘suicide’.

On this subject, the different religions have views that do not coincide.

As far as Christianity is concerned, the position of the Catholic Church has always been very clear. According to Church teaching, suicide is considered a grave sin because it violates God’s commandment that prohibits murder, including murder of oneself.

The Catholic Church has always taught that every human life is a precious gift from God and that we are called to protect and respect this gift. Therefore, suicide is considered an act of contempt towards life and the one who gave it.

However, the Church also understands that, many times, the person committing suicide is afflicted by deep mental, psychological or physical suffering.

14

In such cases, it is recognized that the person may not be fully responsible for his or her actions due to the circumstances.

Furthermore, the Catechism of the Catholic Church states that God is the only final judge of souls and that He alone can fully understand the complexities of the human heart.

However, the Church’s general position remains that suicide is a morally wrong act, as it ends human life voluntarily rather than relying on God’s will.

The Church offers spiritual and pastoral support through prayer, the sacraments and the support of faith communities for those who struggle with the desire to commit suicide, always encouraging them to seek professional help from mental health experts.

For Islam, suicide is considered a grave sin. Islam encourages and supports the respect and protection of life, as it considers it a divine gift. Some Muslim communities view suicide as totally unacceptable, while others see the suicidal person as someone who has committed a sin but may still receive forgiveness from Allah.

Judaism considers suicide as a forbidden act, as it believes that life is a precious good and a gift from God. Some currents of Judaism consider the circumstances that lead to suicide, such as the mental state of the suicidal person, but generally it is considered a negative act.

For Hinduism, suicide is not tolerated and is considered as conduct that leads to the suspension of the cycle of expected reincarnations and can lead to what is called the cycle of suffering. It must be remembered, however, that attitudes towards suicide can vary, as Hinduism encompasses different views and traditions.

For Buddhism, suicide is basically regarded as a negative act because it violates the first of the five fundamental precepts, namely that of not killing. Buddhism regards life as absolutely precious and seeks to find good solutions to life’s various problems.

Those mentioned are not the only religions present on our planet today; think of Sikhism, Zoroastrianism, Shintoism and others. Each of these has its own religious beliefs and practices.

It should also be remembered that within each of these religions there can be different trend lines and interpretations.

—- * —-

Perception of life

The perception of life can change from individual to individual and depend on factors as diverse as personal experience, age, religious beliefs, cultural beliefs, social context and more.

Some may perceive life as a precious gift to be fully appreciated and enjoyed, while others may see it as a burden to be borne or an opportunity to face challenges and overcome obstacles.

Perceptions of life may also be influenced by traumatic events or moments of crisis that may lead to a review of personal priorities and values.

15

In general, the perception of life can be subjective and fluid, changing over time according to experiences and personal perspectives.

Some people may perceive life as an exciting and challenging adventure, while others may see it as a difficult and painful journey.

However, regardless of individual perception, what matters is how one chooses to approach and live one’s life, seeking to find meaning, happiness and personal fulfilment.

—- * —-

Time consciousness

Time consciousness has to do with everyone’s awareness of the passage of time, its importance and its duration. It refers to the ability to perceive the passage of time, to be aware of the past, present and future.

Awareness of time allows us to remember, design and plan our present and our future. It allows us to give meaning to our existence.

According to this work, the lifespan and time consciousness of each human being is configured as a ‘continuum/æternum’, i.e. seamless, made up of infinite segments that have already repeated themselves in our past, repeat themselves in the present and will repeat themselves in our future.

The human or animal, having completed one cycle of life, has no perception of the time that elapses between the end of this cycle and the beginning of the next, however long this interval may last.

Each cycle has, necessarily, had an identical copy in its past and will have an identical one in its future (see the second lemma of the Borel-Cantelli theorem, which gave rise to the tireless monkey theorem).

The reshuffling (between one cycle and the next) at the molecular, atomic and above all sub-atomic level of everything that makes up a human being, an animal, a vegetable or a mineral is such that it can only erase all memory of the lived experience and can leave no trace or memory in its future. This means that each life cycle is perceived, by those able to perceive it, as unique and unrepeatable.

—- * —-

16

Some of the main philosophical currents

The following is a brief and incomplete description of some of the main philosophical currents:

I. Idealism: philosophical theory that holds that reality exists only in the mind or ideas.

II. Empiricism: philosophical current that emphasizes sensory experience as the primary source of knowledge.

III. Dualism: philosophical view that affirms the existence of two separate and independent realities, such as body and soul.

IV. Realism: philosophical view that affirms the existence of an objective reality, independent of the individual.

V. Rationalism: philosophical theory that states that reason and logic are the main sources of knowledge.

VI. Pragmatism: a philosophical current that maintains that the truth of a statement should be assessed on the basis of its practical consequences.

VII. Existentialism: philosophy that emphasizes the importance of the individual in the creation of meaning and existence.

VIII. Materialism: philosophical theory that attaches importance to matter as the basis of reality and existence.

IX. Phenomenology: philosophical method that aims to describe conscious experience without prejudice or assumptions.

In addition to these, there are many others that have developed and spread throughout the history of philosophy. Each of these has its own specific principles and theories that have influenced human thought over the centuries and millennia.

Eternity?

Whether the life of a human being lasts a few years or a hundred years only changes for the number of experiences made, in that particular period/cycle of existence, but not for the quality or even the total duration of life, in infinite time. In fact, a few years or a hundred years are both an infinitesimal of the total passage of infinite time and therefore, both represent nothing more than infinitesimals of this time.

The conclusions of these arguments cannot but leave one breathless, they cannot but amaze and disconcert each of us, since they lead to the affirmation and conclusion that each life cycle of each human being, of each animal or of each plant has already taken place infinite times, in the past, takes place infinite times in the present[17] and cannot but take place, in the future, an infinite number of times.

[17] The conclusions of these arguments cannot but leave one breathless, they cannot but amaze and disconcert each of us, since they lead to the affirmation and conclusion that each life cycle of each human being, of each animal or of each plant has already taken place infinite times, in the past, takes place infinite times in the present and cannot but take place, in the future, an infinite number of times.

17

This means that the sum of the infinite experiences lived in the past added to the present and the infinite future ones, cannot but constitute an eternity, cannot but constitute the eternity of every living being!

The idea of eternity, evoked in all historical epochs, by the various religions and by many philosophers, thus becomes concrete and finds full justification and implementation, through the ‘axiomatic model’ and the present works, which make it their own!

These conclusions cannot but astonish and baffle each of us, since they lead us to affirm and conclude that every life cycle of each human being, each animal or each plant has already taken place infinite times in the past, takes place infinite times in the present and can only take place infinite times in the future.

This idea of eternity, present in human thought throughout the various historical epochs, religions and philosophies, finds a new perspective and a new dimension thanks to the recent ‘axiomatic model/theorem of the infinite Universe’.

This ‘model’, based on solid logical-mathematical and theoretical evidence, confirms and justifies the idea of a ‘Universe’ infinite in time, infinite in the amount of mass/energy and therefore infinite in space.

This new perspective and this new concreteness consist in the fact that for the ‘axiomatic model’, it is not a matter of an eternity of each one’s thought, of the thought lived in the moment before our death.

No! For the ‘model’, it is a matter of a new life cycle from the moment of ‘conception’/’pollination’ to the final moment of death of each living being.

A conception, though not exactly the same, is present and, I believe only for humans, in various spiritual traditions such as Buddhism, Sikhism, Hinduism and some currents of Taoism. In Hinduism, for example, it is believed that the soul goes through many different lives, until it reaches enlightenment. In general, the concept of reincarnation varies greatly from one religion to another and also within different traditions.

In its cosmic reality, this ‘infinite Universe’ of ours is therefore devoid of a beginning and has no end!

Thanks to this ‘cosmological model’, the idea of eternity finally acquires a new dimension and we are able to consider eternity not as a mere metaphysical hypothesis, but as a concrete and tangible physical reality.

In this context, eternity is not just a philosophical or religious concept, but a scientific-mathematical reality that invites us to reflect on the very nature of existence and time. In an infinite and mysterious Universe, eternity finds its space and a new meaning.

There are numerous religions that assure their adherents of eternal, post-death life.

18

One thinks of Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism (particularly Mahayana Buddhism and Vajrayana Buddhism) come to mind. All these religions promise and ensure paradise, to their believers, that is, to those who follow the ritual spiritual practices and precepts of their faith.

In contrast, there are some religions that do not envisage an eternity after death. For example, some forms of Buddhism state that the soul is reincarnated in cycles of birth and death until one reaches Nirvana, a state of total liberation from carnal and spiritual desires and suffering.

Some Hindu traditions believe in reincarnation and the endless cycle of death and rebirth, with no concept of an eternal heaven or hell. Then there are some forms of agnosticism and/or atheism that do not contemplate eternity after death.

The eternity of every being, envisaged by the ‘axiomatic model’, calls for reflection on the meaning that each of us attaches to our lives and the profound meaning of this concept.

The question arises: “what does it matter what each one’s belief is and what great and substantial difference there ever is between the Christian, the Hindu, the Buddhist, the follower of Zoroaster, the atheist and whatever else, …“

—- * —-

The bishop’s Easter conference

In an attempt to search for the roots from which sprouted what became the ‘axiomatic model’ and the present subsequent work, I cannot help but evoke an experience I had many years ago.

It was on the eve of Easter 1968. By now eighteen years old, I had acquired the right to attend the conference held by the new bishop of Aosta Monsignor Ovidio Lari and dedicated to men of age (for women there was a conference dedicated to them).

I had listened with great interest to his speech, as I was looking for confirmation or, possibly, refutation of the ideas I had formed on the existential question and on my beliefs which, lately, no longer seemed so convincing and in respect of which quite a few doubts had arisen.

During his long and impassioned speech, at a certain point Bishop Ovid says: “you have to believe, because…” I was absolutely interested to know the reasons for this “because…” and the Monsignor reveals it with a broad smile and with his well-known and proverbial calm and composure: “you have to believe, because it is beautiful!“

I confess that this explanation, for me, was a real surprise and, at the same time, a tremendous blow.

That ‘because it’s beautiful!‘ had been highly indigestible to me.

19

Today I am a few years older and, since then, a lot of water has passed down there, eighty meters deep, in the two “Dore” (watercourses) that flow on the sides of the capital of the municipality where I live and which, for this reason, has taken the name of Introd, which means: ‘entre-eaux’ (between the waters).

Besides water, much else has passed in all these years and some of the convictions of that time no longer coincide with those of today, although much has remained of those fresh and profound ideas that forged my way of thinking.

Today, and especially as a result of the work that I have decided to call the ‘axiomatic model’, I can say that a certain view of reality and of the ‘world’ in which we live has changed, and perhaps even profoundly.

The reflections resulting from this ‘model’ suggest an attitude that is certainly more cautious and softer than my reaction to that ‘one must believe, because it is beautiful’ of our bishop Ovid. Today, I cannot but have a deep respect for each person’s ‘ belief ‘.

I must admit that this ‘deep respect’ was, albeit to a small degree, influenced by an experience I had in the summer two years ago that deserves to be recounted.

I was sitting in the ‘dehors’ of our house, together with a friend, when two cars arrived (two ‘doblos’), which had to stop because you can’t go any further with that type of vehicle, on the little road that passes near our house.

It used to be the mule track that was used to go to the neighboring commune of Arvier and also to go to the village of Le Combes.

Today there is an alternative route, which is much smoother and well paved.

The ‘Ton-Ton’ of the first of the two ‘doblo’ opted for this route instead, perhaps because it is a little shorter.

I stand up and approach the passengers of the first of the two vehicles, to advise the driver to backtrack (about a hundred meters) to return to the inter-municipal road that connects the two municipalities of Introd and Arvier.

The first of the two ‘doblo’ contained five beautiful nuns who intended to travel to Combes di Introd (about 5 kilometers away) to visit the home of the popes: John Paul IIo and Benedict XVIo. The second ‘doblo’ also contained five beautiful nuns.

When I also tell the young driver of the second ‘doblo’ about the need to reverse in that small road that passes in front of our house, she puts her hands in her hair and, with a frightened air and wide eyes, announces her total inability to reverse in that small road. I offer to take over for the pretty nun at the wheel and she gives me a broad, disarming smile, handing me the wheel. I settle down and can’t help but say goodbye to my four passengers.

I start the reverse gear and, fortunately, the driver of the first ‘doblo’ decides to follow me. Once on the main road, I stop and get out.

20

My four passengers also get out, so they stop clapping, but they do so only to come and hug me and show their joy.

So do the other five beautiful nuns from the first ‘doblo’. I then receive an enthusiastic and cheerful hug from all those ten nuns.

They are so happy with the way things went that they are bursting with joy from all, but really from all pores, and are jumping for joy.

Something like this had not been planned and I really did not expect it.

I was embraced by no less than ten beautiful nuns who were bursting with joy from all sides, because they could now resume their journey to their destination, which was the popes’ house at Combes di Introd.

I return home, but something has happened in me.

This unexpected meeting and above all the joy and vitality of this group lit a candle in me that still shines today!

I tell myself how I could ever tell them the content of what I called the ‘axiomatic model/theorem of the infinite Universe’.

I am convinced that, even if I dared to do so, they would immediately be ready to give me one of their wonderful smiles and could only look at me with some compassion and perhaps embrace me for the second time, in an attempt to offer me some of their inexhaustible, infinite and contagious joy.

—- * —-

Almighty and Omniscient

Like all the inhabitants of our parish of Introd, listening to the Sunday sermons of our parish priest, Fr Aldo Moussanet, concerning the qualities of our supreme God of Christians, namely: “the God, in whom we believe, is omnipotent and omniscient.“, I could not help but express some perplexity and some justified doubts.

I will try to explain the reasons for these perplexities and doubts.

To speak of an ‘omniscient’ entity is to attribute to it the quality and capacity to know ‘everything’, but really ‘everything’! In this ‘everything‘, however, it is not possible to exclude ‘itself’ and therefore an entity, in order to be ‘omniscient’, must necessarily also be able to know ‘itself’ completely, that is, it must be able to know ‘itself’, even at the precise moment in which it exercises this knowledge. Here, however, ‘the kettle falls’ because this conclusion leads to the evocation, necessarily, of a recursive procedure that has no end because it must, of necessity, repeat itself continually and ad infinitum. The notion of omniscience leads, inevitably, to contradictions and generates logical problems when considering complete and instantaneous self-knowledge.

Therefore, for me, it was not possible to attribute to any entity, not even to that God, the characteristic of “omniscient” and, consequently, also of “omnipotent“!

21

I am tempted to ask myself, «what does it matter what each one’s creed is, and what great and substantial difference there ever is between the Christian, the Hindu, the Buddhist, the follower of Zoroaster, the atheist and whatever, …»

“La mort du loup” (the death of the wolf)

In his touching, profound and evocative poem ‘La mort du loup’, Alfred Victor de Vigny: [French writer, playwright, soldier and poet (*1797 †1863)] writes:

… Hélas! ai-je pensé, malgré ce grand nom d’Hommes,

Que j’ai honte de nous , débiles que nous sommes!

Comment on doit quitter la vie et tous ses maux,

C’est vous qui le savez sublimes animaux.

A voir ce que l’on fut sur terre et ce qu’on laisse,

Seul le silence est grand; tout le reste est faiblesse.

Translation into English:

Alas, I thought, despite this great name of Men,

how ashamed of us, idiots that we are!

How we must leave life and all its evils,

It is you who know it, sublime animals.

In seeing what we have been, here on earth, and what we leave behind,

Only silence is great; all else is weakness.

So, I could only remain silent in the face of such profound joy of those ten beautiful nuns.

—- * —-

Who am ‘I‘? / What am ‘I‘?

First person singular of the personal pronoun, this ‘ I ‘ expresses/represents the totality of a wide range of chemical components, including water, proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals and various systems: muscular, cardiovascular, nervous, … that is to say, it is everything of which this ‘ I ‘ is made (organs, molecules, atoms, sub/atomic particles, memories, thoughts, joys, sufferings…).

‘ I ‘: am a living organism endowed with feelings that remembers, forgets, rejoices, suffers, labors, loves and sometimes even gets angry.

Since:

– every instant, and therefore also the present one, is generated by what was in the instant immediately preceding it, i.e. by its nearest past, in a πάντα ῥεῖ (Democritus’s ‘panta rei’: ‘everything passes away’) incessant and uninterrupted…

it turns out that:

– this ‘ I ‘ can only follow an obligatory path and even if, at times, it has the impression that it can do what it wants, every now and then it remembers that it cannot help but want what it wants!

22

The freedom of our actions

The concept of cause and effect[18] is a fundamental principle that governs not only physical nature, but also our daily lives and our future. According to this principle, the past cannot be changed and directly influences the present and, consequently, the near future.

Based on this premise, it is important to understand that the actions and choices we make today are the direct result of past experiences and circumstances.

The nearer future is therefore strictly and uniquely dependent on the conditions of the present, which in turn is strictly and uniquely dependent on the conditions of its nearer past.

It is important to remember that the cause-effect principle does not only concern individual actions, but also collective and social dynamics.

Political, economic and social decisions have a direct impact on our lives and our collective future.

In conclusion, the cause-and-effect principle reminds us that every action has consequences and that it is important to be aware of what we do and the implications of our ‘pseudo-choices’ in order to be able to achieve what is in our desires.

These ‘pseudo-choices’ remind us that being able to make our own decision in complete freedom is nothing more than a wonderful, extraordinary, and precious illusion, which we do not know and, above all, do not want to do without!

—- * —-

Grudge? Revenge? Forgiveness?

According to the ‘axiomatic model’, it would be desirable to banish: animosity, resentment, revenge, retaliation and whatever else has to do with behavior that is inspired by punishing someone and for something.

What happened belongs to the past and could not, in any way, not have happened.

I realize that all our behavior, whatever it may be, is destined to become part of the past.

This does not detract from the fact that we, on the basis of impulses from our immediate past, help to shape this future of ours.

[18] This ‘cause-and-effect principle’, also known as the ‘causality principle’, is a foundation of philosophy and science that holds that every event has a cause or set of causes that precede and determine it. This principle has never been disputed with absolute certainty and is one of the fundamental concepts on which much of human knowledge and scientific research is based. It should, however, be noted that there are different interpretations and approaches to causality, and that some philosophical and scientific theories seek to challenge specific aspects of the ‘cause-and-effect concept’.

23

Forgiving does not necessarily mean forgetting what happened but, rather, accepting the situation for what it is and what it was and allows you to lift yourself from the negativity that can arise from resentment and anger.

In Christianity, for instance, forgiveness was recommended by Jesus Christ and deemed absolutely necessary to achieve one’s salvation.

In Islam, the importance of forgiveness towards others is taught in order to obtain mercy from the supreme Allah, and so in many other religions.

Also in Buddhism, forgiveness is considered important for achieving inner peace and overcoming suffering and pain. Forgiveness is generally regarded as an act of compassion and great generosity, which brings inner peace and gratifies both the forgiver and the forgiven.

Forgiveness does not require one to forget what happened, but to accept the situation for what it is and what it was and allows one to relieve oneself of the negativity that can arise from resentment and anger.

Forgiveness can bring inner peace and emotional restoration, allowing one to overcome past sorrows and move forward with a more positive and constructive outlook on life.

Thinking about the infinity of a Universe, our Universe, is a fascinating and at the same time shocking idea, but we cannot ignore the fact that, for the ‘axiomatic model’, the existence of a Universe infinite in time, in the amount of mass and energy, and in space is a reality, a demonstrable and proven reality[19].

After rereading the “axiomatic model”. From which the present work draws inspiration, I cannot help but report its penultimate paragraph which reads as follows: « The fact of feeling, ideally connected with the entire infinite Universe made me forget the idea I had previously, that is, of being nothing but a small, small and absolutely insignificant grain, in this infinite world! »

—- * —-

Small, small?

Thinking about a Universe infinite in time, infinite in the amount of mass/energy and therefore infinite in space, without boundaries, makes us feel small, small and insignificant, but at the same time allows us to reflect on our role in this vast and mysterious Universe.

Thinking about the infinity of this Universe is certainly exciting and very fascinating, but it requires, without a doubt, a strong dose of humility to admit that we are small, but really small, and that our laws of physics, conquered with difficulty over centuries, indeed millennia, describe no more than a small, tiny part of an infinitesimal part of this infinite Universe of ours.

[19] See, in particular, the chapter: “There is a Universe infinite in time, infinite in the amount of mass/energy and therefore infinite in space.”

24

After rereading the “axiomatic model“, from which the present work draws inspiration, I cannot help but report its penultimate paragraph which reads as follows: «The fact of feeling ideally connected with the entire infinite Universe made me forget the idea I had previously, that is, of being nothing but a small, tiny and absolutely insignificant grain in this infinite world!»

—- * —-

The “Principle of Cause and Effect”

In the ‘axiomatic model/theorem’, it is shown that it is neither thinkable nor possible to deny this principle (cause-effect).

Denying the principle of “cause and effect” is impossible, since it would imply the need to invoke some form of “creation” and this ‘creation’ could only conflict with and contradict the first axiom of the ‘axiomatic model‘: ‘nothing from absolute nothing …‘ which is ‘the principle of conservation of energy or mass‘.[20]

I have always been deeply puzzled and amazed by certain statements made by Richard Phillips Feynman, Nobel Prize winner in 1965, for his contribution to the development of quantum electrodynamics. He was quoted as stating:

– “If you think you have understood quantum theory, it means you have not understood it!“

And again:

– “I think I can state that nobody understands quantum mechanics.“

Thus, every ‘state/effect‘[21] depends on at least one or a plurality of ‘states/effects‘.

Possible ‘entanglement’ effects cannot be excluded. Quantum entanglement {quantum correlation} does not violate or negate the principle of causality. A ‘state’ {state, temperature, energy, relative position, …} depends on another ‘state’ or ‘other states‘. According to quantum mechanics, physical systems evolve deterministically within ‘Hilbert spaces‘[22].

The ‘cause-effect principle’ is one of the fundamental concepts in logic and philosophy that establishes a direct relationship between a cause and its effect.

This principle goes beyond the mere observation of concurrent events, but suggests that there is a deterministic correlation between a specific cause and the resulting effect.

The validity of this principle is fundamental for understanding the world around us and for predicting the future. If we accept that every event has a specific cause, we can use this principle to anticipate the consequences of our actions and to make informed decisions.

[20] Theories of ‘hidden variables’ are being developed that seek alternative solutions to certain assumptions of quantum mechanics, considered by many to be incomplete.

[21] Proper subset, not null, of the infinite Universe, also taken as small as desired.

[22] Hilbert spaces are vector spaces that have a particular geometric structure defined by an inner product. This inner product allows concepts of length, angle and distance to be defined within the vector space. Furthermore, Hilbert spaces have mathematical properties that make them particularly useful in various fields of mathematics, such as functional analysis and optimisation in general.

25

For example, if we want to achieve a specific goal, we can analyses the possible causes that could lead to that desired effect and act accordingly. In this way, we can increase the probability of success and achieve our goals more effectively.

Furthermore, the ‘cause-effect principle’ helps us understand the complex relationships that govern the natural and social world. By studying the causes that lead to certain effects, we can identify the mechanisms that govern reality and take targeted action to improve our living conditions.

In conclusion, the validity of the ‘cause-effect principle‘ is essential to our reasoning and our ability to actively influence the world around us. Accepting this principle allows us to be conscious agents of our reality and to achieve our goals more effectively.

—- * —-

Denial of the existence of ‘free will’

Free will’ cannot exist. The question of ‘free will’ is, and has long been, a subject of debate and controversy. On this subject, there are different views supported by scientific, psychological and philosophical arguments.

There are those who argue (and among them, the ‘axiomatic model’ itself) that free will is a complex illusory perception and that all human conduct, and not only that, is determined by specific causes and conditions. According to this view, the choices and decisions that are made are explained and predicted by events that took place in our closest past.

Many people firmly believe in the existence of free will and the ability to make independent decisions without external constraints.

However, upon careful reflection on this concept, one realizes that it cannot actually exist.

Firstly, the concept of free will implies that we are able to make completely autonomous choices, independent of external factors.

But the reality is that our decisions are influenced by a myriad of factors, both genetic and environmental, that limit our freedom of choice.

Furthermore, scientific research has shown that many of our actions are the result of unconscious brain processes, which occur long before we become aware of our decision.

This means that our sense of control over our actions is often an illusion.

Finally, the idea of free will is often used as an excuse to justify immoral or harmful behavior, as it is believed that everyone has the possibility of making positive choices.

It is surely worth reflecting on how far our freedom of choice can go, since we may be free to do what we want but we cannot help but ask ourselves: ‘are we really free to want what we want?

In conclusion, the denial of the existence of free will does not deprive us of our humanity or the ability to make meaningful decisions, but it does prompt us to consider our actions and their causes more realistically.

26

Let us therefore stop deluding ourselves that we are the only masters of our choices and accept the reality around us.

On p. 86 of his book ‘Physics and Philosophy’ Werner Heisenberg writes: «Therefore, in order to safeguard the complete parallelism between mental and physical experiences, the mind too had to be in its activity completely determined by laws that corresponded to those of physics and chemistry. And here arose the problem of the possibility of free will. This whole system appears rather superficial and reveals the great defects of Cartesian dualism…»

Cartesian dualism is a philosophical theory developed by mathematician, philosopher and scientist René Descartes (*1596 †1650) in the 17th century.

In his treatise: ‘Discours de la méthode’ (Discourse on method) and in his ‘Principes de philosophie’ (Principles of philosophy), Descartes assumes the existence of two basic and differentiated substances: ‘res extensa’ (matter in space) and ‘res cogitans’ (the human spirit and mind).

According to Descartes, matter is an ‘extended substance’ that does not have the faculty of thinking and does not possess consciousness. Mind, on the other hand, is a non-material essence that has the ability to think and possesses a consciousness of what it does.

This Cartesian dualism has greatly influenced the philosophy of our Western world and contributed to the development of debates concerning the relationship between the material body and the immaterial mind.

Descartes analyzed in depth what he called ‘the problem of communication’. This concerns the question of how the body can influence the mind and, in turn, how the mind can influence the body.

This ‘Cartesian dualism’ stimulated intense debate, and also provoked strong criticism, from philosophers contemporary and posterior to Descartes, who were convinced that the separation between the body and the mind could not be so radical, since a relationship of correlation and interdependence must, of necessity, exist between the two.

27

Huygens or Newton ???

Regarding ‘Cartesian dualism’, it must be said that the concept of ‘waviness’ was first introduced by Christiaan Huygens (*1629 †1695), Dutch physicist, mathematician and inventor) in the 17th century. Huygens was a member of the Royal Society of London. He claimed that light propagates through a transparent medium in the form of waves and in a ‘wave-like’ manner. Isaac Newton (*1643 †1727), on the other hand, supported the corpuscular nature of this light. on page 37, it reads:

In his book ‘THE PARTICLE AT THE END OF THE UNIVERSE’, Sean Carrol (born 1966, American theoretical physicist known for his contributions to theoretical physics, in particular his research into elementary particle physics) writes:

«The world is made up of ‘fields’: entities spread throughout space that manifest themselves to us through their vibrations, which appear to us as particles. The electric field and the gravitational field might sound familiar, but according to quantum field theory, even particles such as electrons and quarks are actually vibrations of certain types of fields.

The Higgs boson is a vibration in the Higgs field, just as a photon of light is a vibration in the electromagnetic field.»

Many philosophers argued for the existence of ‘free will’ because they were deeply convinced of the fact that human beings have the possibility and the ability to make conscious choices in an autonomous manner, free from external influences.

This way of thinking is essentially, though not exclusively, based on religious and/or moral arguments, while others may argue its non-existence on the basis of scientific or philosophical arguments.

The ‘axiomatic model’ and thus also the present work cannot but be in agreement with the principle of cause-effect. If an event, taken as small as one likes, let us call it: ‘epsilon’ (ε), were able to violate this principle, then it would mean that (ε) or a part of it, would be deprived of that complete connection to their closest past.

Thus (ε) or a part of it would be devoid of an origin, but this would mean that (ε) or a subset of it would necessarily have to have the characteristic of a creation. ‘Creation’ is and is recognized by science as pseudo-science, i.e. false science, and therefore cannot be invoked to justify a non-existent and impossible ‘free will’.

—- * —-

Intuition

Since, in the realization of the ‘axiomatic model’, there is a component that has played an absolutely prominent role, and which has not been mentioned, I would like to address, in this paper, some reflections on the issue of intuition.

28

Despite what one reads in many quarters, it seems to me that there is a substantial difference between ‘quantum mechanics’ and ‘intuition’. Quantum mechanics’ finds application in the atomic and sub-atomic world, i.e. near that boundary which, in the direction of the infinitely small, separates the world of the known, studied and described by classical physics from that world which is still not sufficiently known (essentially because of Heisenberg’s ‘uncertainty principle’). This ‘quantum mechanics’ has its own laws and theorems, which are often not very intuitive and, therefore, not easy to understand.

In this connection, it should be remembered that the theoretical physicist (Nobel Prize winner for physics in 1965) Richard Feynman had this to say: ‘If you think you have understood quantum theory, it means that you have not understood it!’ and again: ‘I think I can say that nobody understands quantum mechanics’.

It cannot be ruled out then that ‘intuition’ could even lie beyond this boundary, in a territory of which, today, we know practically nothing. We do not know its extent, we do not know its theorems, we do not know if it has any and we do not know the laws that govern it.

That is why, there may be a substantial difference between ‘quantum mechanics’ and ‘intuition’.

The mathematician Kurt Gödel (*1906 †1978) saw mathematical intuition as a form of real, and not purely abstract or conceptual, knowledge.

With his enunciation of the incompleteness theorems, according to which the truth underlying a formal system cannot be proven from within the logical system itself, he probably intended to refer to the logical path already used by Plato (*428/427 b.c. †348/347 b.c.).

For Plato, intuition is a capacity of the human mind that allows access to universal and immutable truths that lie beyond the sensible world.

A hypothesis that is impossible to verify and may appear somewhat fanciful suggests the idea that this intuition has to do with some form of recollection of experiences lived, in infinite numbers, in our past. See Poincaré’s recurrence theorem and the second lemma of the Borel-Cantelli theorem (tireless monkey theorem). This hypothesis, suggestive and certainly stimulating, would invoke something to do with one or more of the many ‘fields’ that permeate our Cosmos and, more generally, our infinite Universe.

One thinks, in particular, of

– to the Electric Field, which describes the interaction between electric charges,